By Wayne Allensworth

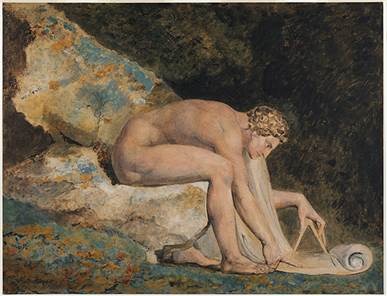

William Blake’s Newton (1795)

He [Newton] seems meant to be associated with the rock on which he sits, emphasizing Blake’s view that the laws of Newtonian physics had fixed the world in Urizenic petrification, as later stated in A Descriptive Catalogue: “The Horse of Intellect is leaping from the cliffs of Memory and Reasoning;

it is a barren Rock: it is also called the Barren Waste of Locke and Newton”

— Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly

I visited our city’s landfill recently, loaded down with the detritus of our mass production, mass consumption world. Cans, some of them full. Never opened. “Junk” as in items nobody wanted or needed any longer — and maybe never really did. And the inevitable piles of trash. The landfill had a section for discarded bicycles, electronics, and TV sets. At home, we have boxes of stuff, some of which we never unpacked from moving 24 years ago. Our closets are stuffed full — and I recently noticed that I only wear a few of the dozens of shirts I own.

Is there some happy medium between privation and the equivalent of consumerist gluttony? The only resolution I can see at present is self-discipline. Restraint. “Delayed gratification” as it were. But there is more to it than that. Just as we have become prisoners of our own technologies, we can become the servants of our things. Our stuff. Or, rather, the insatiable desire for more stuff. The old adage “money doesn’t buy happiness” could be “more things won’t make you happy,” for the pursuit of money is inevitably linked to a desire for things, even if the ultimate “thing” is status. Judging by the world I see around me, “liberation” from the old morality, from duty taking precedence over desire, and prudence yielding to self-realization — or just plain old greed — has not only not made us happier, it seems to have made many of us miserable. Immediate gratification is the result of a form of gluttony that ends where materialism — as a pursuit and a philosophy — always ends, with boredom, even depression at the emptiness of it all. The new wears off one thing, so we look for another that would temporarily give us a rush. But it usually doesn’t last.

In managerial capitalism, each of us is a unit of production and consumption. We are cogs in a vast socio-economic machine built on debt, for our desires usually outpace our ability to fulfill them, and usury, neither of which formerly had a good reputation. Monetary devaluation seems concomitant with such a system. As the currency is debased, and inflation is spurred on, the costs of materials for production rise and producers take short cuts, undercutting the quality of their goods. The things we love break, and we throw them away and get another thing. It’s no accident that the most reliable appliance we own, a refrigerator, is about 60 years old. I know there are exceptions, but building things to last a lifetime doesn’t pay for producers.

Consumer “demand,” or desire might be a better word, is related to mass culture and mass media. People have always delighted in their things, their belongings, and in the status that prestigious things bore with them. But hard money and limited production capacity restrained that impulse with some equally hard reality. I don’t know where the lines between privation, unfulfilled wants and needs, and debt fueled consumption are. It’s a continuum. And I don’t think that the complaints of young people loaded down with college debt (we told them they had to go, remember?), limited by fewer job opportunities, lost in a sea of mass immigration (our children must compete with the whole world, even at home), and soaring prices are unjustified. To the contrary, those problems must be handled if we are to have a future. But paradoxically, the consumer machine rolls on.

It rolls on because the machine via mass advertising, “social media influencers,” and Instagram culture, a culture of ever shifting images and sound bites, feeds the overstimulation that mass culture nurtures. The machine’s mission is to stimulate demand — desire — with novelty. We are easily bored and a fleeting rush of acquisition of one new thing quickly melts into familiarity and indifference. New stimulants are required, as with drug addiction, when new levels of the high have to be reached. Or pornography, in which ever more depraved scenarios are also required. Each step along the path is more dehumanizing, creating a wider gap between humanity and the natural world of which we are a part, and in some cases, between ourselves and other actual, not virtual, human beings. We jump on the treadmill of pleasure seeking. And it’s difficult to get off.

The flip side of constant pleasure seeking can be risk aversion. Why risk rejection in an actual relationship with another human being? Friendship, romance, filial obligations, bring with them the terrible downside of possible rejection, of the breaking off of attachments, and, ultimately, of death. Yet those risks are what make our personal development possible. For the first time in human history we can avoid — or have the illusion of avoiding — personal loss. But the real loss is our own soul. Mephistopheles is all-too-ready to seal the deal and make the exchange.

The machine demands that we “produce,” that we never stop producing and consuming. We have been misdirected onto a lost highway to nowhere. The production and consumption machinery has been around for a long time, but not like today, when we carry little computer screens around with us. Built to reward repetitive behavior like slot machines, they generate stimulating images, making it hard to resist checking that screen constantly. But in my lifetime, the “Madison Avenue” advertising industry worked hard to whittle away at the values of my parents and grandparents, who would use something until it finally broke down completely, then sometimes still found a way to keep it running for a while longer. They valued the first new car they had ever owned, or acquiring a color TV, an amazing novelty.They used to fix a broken toaster; today, we simply throw it away and get another one at Walmart. But the old ways had to be actively undermined and attacked directly. The upheavals of the 1960s did a lot to further that aim.

New technologies, the machines themselves, carry their ideology, a Zeitgeist of transcendence of the human condition with them. The Internet is a rejection of limitations of space and time. Urbanization, stimulated by productive capacity and industrialization, moved production out of the home, out of the workshop, and into assembly lines. Mass culture and fragmentation were embedded in the trajectory of the new world.

More than 200 hundred years ago, as the industrial revolution transformed Britain, the poet and engraver William Blake foresaw the end game of societal transformation in nihilism. Blake sensed the implications of Newtonian physics: The world is a machine, operating by “laws” that pre-determined outcomes. If Newton saw those laws as God’s work, it was the work of a great engineer, implying that we were automatons in the vast clockwork of the cosmos. The Great Watchmaker was soon cast aside as unnecessary, as “blind” and detached from the universe. The new age of technocratic bureaucracy and industry didn’t really need Him. “We” erroneously believed we had cracked a once secret code, and could manipulate and control our environment, which quickly became viewed as a cache of resources in a utilitarian worldview. The alchemy was in our machines. It wasn’t just a disenchantment of the world, but a misenchantment, mistaking the purely mechanical for something that ultimately would give us the power to become gods ourselves. To make gold from base metals. With what he called his perceptive “second sight,” or gift of insight that could see beyond surface reality, Blake understood that the great longing that all humans had for the divine could be supplanted by a shallow desire for things. It was a torturous and destructive addiction. It would erode and ultimately destroy our spiritual sense, our collective second sight. He called proponents of materialism “Enemies of the Human Race.” His remedy was to harness our longing and redirect it towards its proper aim.

To be sure, Blake the engraver prospered in the new money-driven economy. But he was well aware of the temptations that came with it:

Get thee away! Get thee away!

Prayest thou for riches? Away! Away!

This is the Throne of Mammon grey.

Said I, this sure is very odd.

I took it to be the Throne of God.

For everything besides I have:

It is only for riches that I can crave.

Blake was aware that the best things in life are free. That human ties were his actual riches:

I have Mental Joy & Health

And Mental Friends & Mental wealth

I’ve a wife I love and that loves me;

I’ve all But Riches Bodily.

Blake proclaimed,

And so you may do the worst you can do:

Be assur’d Mr. Devil I won’t pray to you.

The great poet, Blake biographer Mark Vernon wrote, had concluded that “Money is indeed the root of all evil when it separates us from felt relationships in a teeming world.” Blake also understood the radical implications of managerial materialism when applied to politics. Thomas Paine, a man about whom Blake had decidedly mixed feelings, had proclaimed that “we have it in our power to begin the world over again;” that is, to not simply reform a flawed system, but wipe the slate clean for the new scientific elite to create a new one. Blake was hardly a reactionary, and noted that absolutists of all types, including monarchists, transcendently justified their supreme power. But he mocked the “Lunar Men,” of the British Lunar Society, a monthly gathering of the new elite that included Erasmus Darwin and James Watt, fearing industrial “Satanic Mills” on the historic horizon, the cosmos cast as a great machine and we ourselves as mechanical beings, the “meat computers” of the “New Atheists.”

To covet another’s possessions is a sin. Coveting is a deep, intense, and unhealthy desire for what belongs to someone else. It is an impulse driven by envy, one that could lead to destructive behavior. Consumerism is fueled by something that approaches that — recall “Keeping up with the Joneses” — matching, or topping, the material possessions of others in a social hierarchy based on material status. The tenth commandment is about one’s motivations that are so revealing if brought to the light of day.

Many of us still can’t grasp that a nation is a community of people joined by language, ethnicity, religion, and customs, and not a giant big box store for a reason. In the centuries since Blake observed the profound moral peril of worshipping Mammon, we have adopted the mechanical Economic Man worldview. How many times have I heard Americans proclaiming their patriotism in terms of living standards, GDP, or material wellbeing? High-flying Top Gun militarism and chest-beating about technological achievements follow from that. But even if America had never landed on the Moon, or achieved such soaring heights of material achievement, even if she had never been a superpower, a state I lament, I would still love her and her people, as they are mine. They are my country, my people, my family. I have mental joy and mental health, friends and wife and children and their children. All of us should echo Blake’s words:

I am in God’s presence night and day,

And He never turns His face away;

The accuser of sins by my side doth stand,

And he holds my money-bag in his hand.

For my worldly things God makes him pay,

And he’d pay for more if to him I would pray;

And so you may do the worst you can do;

Be assur’d, Mr. Devil, I won’t pray to you.

Chronicles contributor Wayne Allensworth is the author of The Russian Question: Nationalism, Modernization, and Post-Communist Russia, and a novel, Field of Blood. For thirty-two years, he worked as an analyst and Russia area expert in the US intelligence community.

Please consider supporting American Remnant: A green “Donate Today” button has been added at the end of each article (see below) appearing on the website. If you value what AR is doing, please consider supporting the website financially. $5, $10, or any amount that you can afford. Regular donations would especially be appreciated. Thank you!