By Wayne Allensworth

On Christmas Eve, 1968, the crew of the Apollo 8, Bill Anders, Jim Lovell, and Frank Borman, read verses 1-10 of the Genesis creation narrative as they orbited the moon:

We have lost the sense of wonder, of enchantment with and in our world. So many of us have become enveloped in a technological cocoon that regaining it will be difficult. Man has successfully manipulated his environment to such a point that humanity—or a substantial portion of humanity—no longer believes that it is bound in any way by the limitations of our nature, or our bodies. A young man or woman in the 21st Century can grow up, graduate from school, and begin their working lives in a largely controlled environment. Direct contact with the natural world is truncated to such a degree that many of us can live out a large segment of our time in a manipulable—and manipulative—tech bubble, one that lends us the illusion of omnipotence. Immediate gratification, as fleeting as it is, is readily available, leading to the next click, the next channel surf, to find that momentary stimulus that can make us all tech addicts, unable to enjoy a slow walk in the daylight, feel the sun on our backs, the wind in our hair, and the hand of something transcendent we no longer have a name for.

The illusion of total control is ascendant, permeating everything in our culture. We imagine that we can chose everything about ourselves, and even dream of digitally transcending our flesh (“trans-humanism,” the next step on the “trans” scale of being), all of it based a mechanical view of humanity as a mass of “meat computers” that can be reprogrammed. The story of how that happened is a long one, but suffice to say that Newton’s physics, which he thought of as a means of reading the mind of God, was quickly abridged by an emerging scientism, not science or the scientific method, but a Promethean ideology that projected an eventual technocratic Utopia.

It’s the old story—ye shall be as gods—a rebellion against walking the straight and narrow path that our traditional religion has told us is the only way to life. It’s a way, however, that requires the paradoxical acceptance of bearing one’s cross, accepting suffering, of sacrificing ourselves in a certain sense, in order gain life. Experience should have taught us by now that straight is the path, and narrow the way to a life with meaning, and that taking another path, a path ideologues have tread since at least the French Revolution, is the way to dusty death.

Our sense of the transcendent remains. It has simply been redirected, taking on new forms. That should tell us something about our nature, our consciousness, and our intuitive religious sense, a sense of awe that shows up again and again in myths and religious texts, along with what C. S. Lewis called “the Tao” , or natural law, in cultures around the world. It wasn’t something worked out by a committee, or rationalized, but was based in experience and practice over vast periods of time. A fundamental assumption underlying the Tao is a rejection of mechanistic materialism. We can’t or won’t rely on that intuitive sense any longer, but it won’t leave us alone. So, we hide it in the cloak of scientism, rationalism, and high-tech fantasy.

As I was walking out of a movie theater in 1968 or ’69, I recall a man in the crowd asking, “What was that all about?” We had just seen a screening of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, a space age movie that fascinated the boy me, who had pictures of America’s—and my hometown of Houston’s—newest heroes, the astronauts, in my room at home. It was a memorable two and a half hours—the theatre was one that still had one huge screen, with an elaborate sound system that wrapped the audience in a total sensory experience. It was an experience that can’t be reproduced by television, much less cellphone, screens. The fact that Kubrick’s film enraptured, fascinated, frustrated, and engaged audiences at such a profound level, and that it remains a classic, was evidence that he had struck a nerve. At the time, I was impressed by the film and all the neat sci-fi effects, but it would be decades before I could put my finger on why 2001 had such a magnetic quality that drew in audiences who left the theatre puzzled, perhaps, but nevertheless mesmerized by Kubrick’s vision.

It was another movie, Stephen Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, released in 1977, that set the wheels turning in my still immature mind, and subsequent viewings fleshed out the vague sense I had that Close Encounters was deeply religious in its imagery and theme. Roy Neary, an electrician played by Richard Dreyfus, begins having visions after a number of people, including Roy himself, have “close encounters” with UFOs. Roy envisions a high place, a mountain top, and begins obsessing about it, making clay models of the high place. His wife believes he is becoming psychologically unhinged. Roy, along with another visionary, Jillian, evades the authorities who have closed off approaches to Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, where a team of scientists expect to contact extraterrestrials. In the end, Roy is whisked away by the aliens, wafting into space on the greatest journey of all.

(pinterst.com)

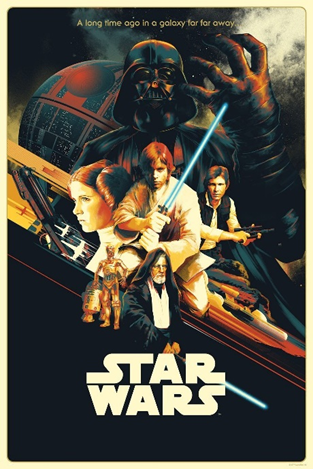

Recall that 1977 was also the year that the original Star Wars film, one that draws heavily on mythic and religious themes, was released. I’m not sure when all this coalesced in my mind and I realized what I had witnessed in those two movies, and earlier in 2001, but it eventually dawned on me that Roy the visionary was a prophet, the high place a space age Mount Sinai, the aliens angelic messengers, the family that rejected Roy a stand in for those who rejected the prophets of the past, and Roy’s joining the crew of the alien Mother Ship, an ascension. Roy had essentially been transformed by a deeply religious experience. The musical tones that announced the aliens/angels were the voice from the Burning Bush or perhaps, a Vedic mantra.

(reddit.com)

In 2001, Kubrick had already plowed religious ground, with aliens (angels) projecting a vital (divine) force (George Lucas had undoubtedly been as mesmerized by 2001 as I had been) that in effect creates the human race, an idea popular with some scientists—how else to explain the miraculous circumstances surrounding the creation of our universe and us?

At the end of the film, astronaut Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) is transfigured after passing through a psychedelic tunnel (or underworld), emerging as the Star Child, or new Adam or Nietzschean Superman, take your pick. He orbits around a new Earth in a new Heaven. And that is Man’s Fate. Dave joins the now purely spiritual beings who have evolved beyond the biological to a new level of consciousness.

(stepkid.com)

I’ve often wondered whether the claims of numerous people to have been taken captive by aliens were distorted visions of the kind of angelic creatures prophets and mystics had reported for as long as religious traditions have existed. The dream of transcendence, the hope for something beyond, the longing for the divine, has never left us. The dreams of fantasists, sci-fi writers, and film makers have wrapped those deeply human impulses in the only language and imagery acceptable in an age of scientism. It was no surprise to me to learn that Kubrick had once reportedly described the angelic aliens of 2001 as “immortal machine entities” that then transcended even that, becoming beings of “pure energy and spirit.” It’s also appropriate that the second act of 2001, in which Dave struggles with a recalcitrant supercomputer (“HAL”), carries with it a warning: Our machines might make prisoners of us. Our own Promethean desires may as well.

I recall Jordan Peterson once quipping that he was amused by techie Star Wars fans who claimed they were atheists, then stood in line for hours, if not days, to purchase tickets for the next installment of George Lucas’s religiously-themed space epic. Peterson was on to them. They deny what they call “the supernatural,” but deeply desire divinity on their own terms, terms that do not demand the sacrifices necessary to follow the narrow path. I understand. It isn’t easy to pick up one’s cross and voluntarily take that path. It’s all too easy to imagine that we can have our spiritual cake and eat it, too, without submitting to something greater and more awesome than our sci-fi fantasies can conjure up, something that is not mechanical, something not subject to our manipulations.

What will it be, angels or spacemen?

Chronicles contributor Wayne Allensworth is the author of The Russian Question: Nationalism, Modernization, and Post-Communist Russia, and a novel, Field of Blood.